Nobody Enforces Least Privilege Because Nobody Wants to Be the One Who Breaks Things

Everyone talks about it. Few implement it. Fewer enforce it.

Palo Alto Networks found that 99% of cloud users were granted excessive permissions, and 95% of those permissions were never used. It’s the kind of stat that should set off alarms. But if you’ve worked in engineering or security for more than a few weeks, it probably doesn’t surprise you. We all know that permissions sprawl. We just rarely talk about what that means, or why it happens in the first place.

At one job, I discovered an API key embedded in a CI pipeline that had write access to production and hadn’t been rotated in over two years. It had no expiration policy, no logging, no documented owner. When I brought it up during review, the response was exactly what you’d expect: “Oh yeah. We should probably do something about that.”

But we didn’t. It wasn’t urgent. No one wanted to touch it right before launch. And so it stayed.

This is the quiet failure of least privilege — not the dramatic headline-grabbing breach, but the gradual erosion of access discipline, one overlooked key or overly permissive IAM role at a time. Everyone thinks they’re enforcing principle of least privilege. Very few teams actually are. Even fewer can prove it under scrutiny.

In theory, least privilege is a security fundamental. In practice, it’s a collective fiction: a policy we declare but rarely audit, a posture we believe we have because our compliance checkbox says so.

This essay is about that gap — the space between what we say we’ve secured and what’s actually reachable with three clicks and the wrong credentials. It’s about the social dynamics, technical debt, and institutional incentives that make least privilege difficult to achieve and nearly impossible to enforce at scale.

And it’s about why the problem isn’t always just the tooling — it’s us.

The Security Ideal We Pretend Exists

Ask anyone in security engineering what the principle of least privilege means, and they’ll give you the textbook answer: users, services, and systems should only have access to what they need — nothing more, nothing less. The idea is simple. It’s one of the core tenets of zero trust. It’s baked into every vendor pitch, every compliance framework, every onboarding deck. In theory, it’s obvious.

In practice, it’s performative.

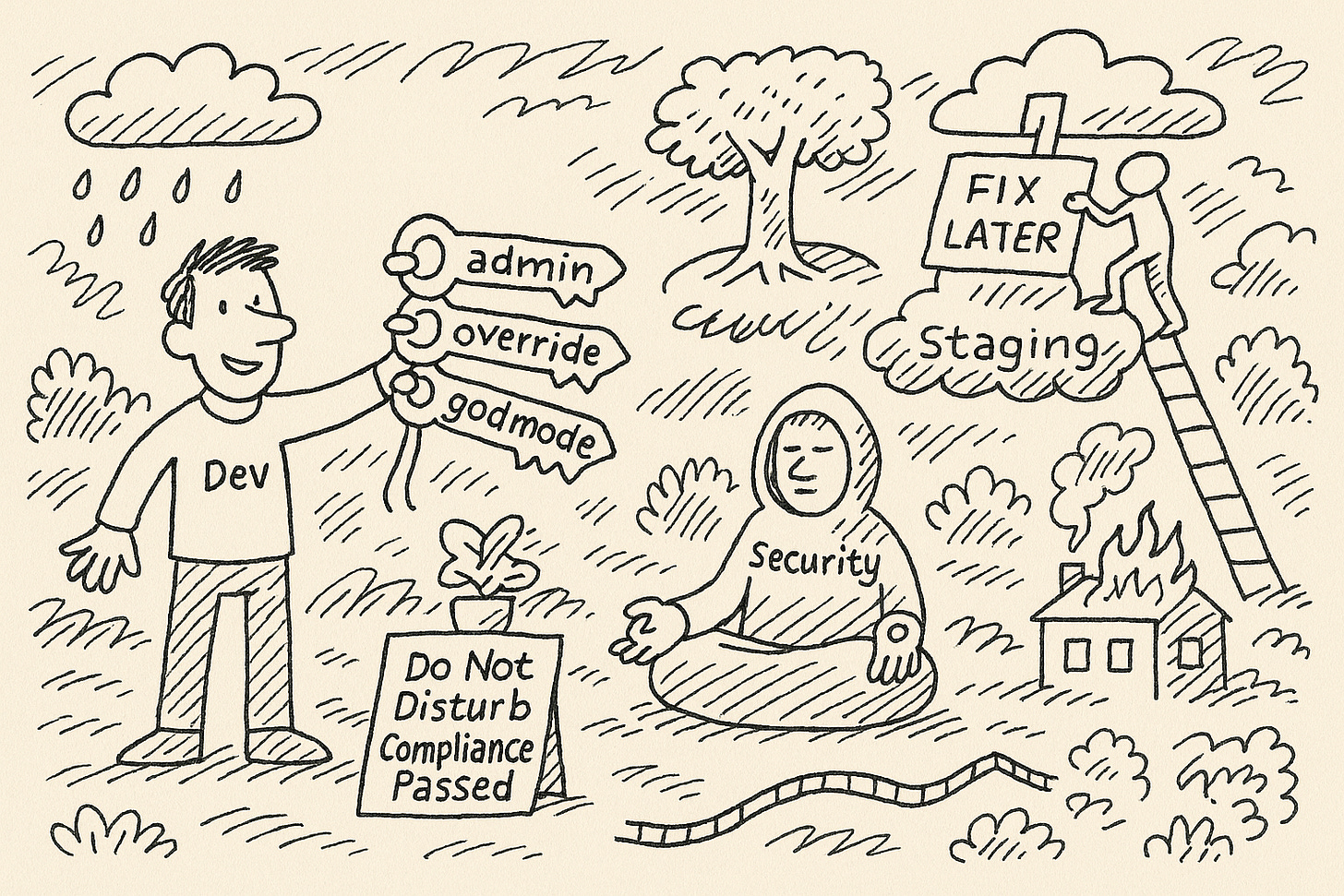

At scale, least privilege isn’t a default — it’s a daily act of resistance. One that gets harder every time a product team shortcuts an access request to hit a deadline, or when an engineer copies a permissions template without knowing what it actually enables. You know the ones: roles named PowerUser, AdminClone, or FullAccess_Override, quietly created months ago and now too risky to delete.

Everyone pretends the system is under control — until someone runs terraform destroy in production, or a support script accidentally wipes customer data, or a leaked token gives an intern godmode access to cloud storage.

And it's not just anecdotal. IBM’s Cost of a Data Breach report found that 83% of organizations experienced more than one breach, and in nearly half of cases, the root cause was traced back to overly broad access. Not malware. Not zero-days. Just normal people with too much reach.

The irony is that most of these systems were designed with controls in mind. There were RBAC policies, audit logs, role hierarchies. But those controls were fragile from the start — either misunderstood, misapplied, or quietly sidestepped in the name of velocity.

This is where the fiction kicks in: when least privilege exists only in policy but not in code, config, or culture. It’s something we say to auditors and regulators, not something we practice in architecture or incident response.

The problem isn’t that we don’t believe in least privilege. It’s that we keep pretending we already have it.

The Everyday Reality

No breach starts with a big red button. It starts with a shortcut.

It starts when a developer needs access to a new data source — and the fastest way to unblock them is to clone the permissions from another role. Not the right role, just one that works. Maybe someone will come back and tighten it later. But of course, they won’t.

It starts when a vendor integration fails in staging, and the fix is to grant temporary write access to production. The team swears it’s just for testing. There’s a Jira ticket to revoke it. That ticket gets marked as “Won’t Do” six weeks later.

It starts when a senior engineer wants to move faster and asks for blanket access “just for now.” They get it. Because no one wants to slow them down. Because they’re trusted. Because they know what they’re doing — until they don’t.

It starts with a role that no one created, no one maintains, and no one understands — but that still has access to core infrastructure. Someone tries to delete it during a cleanup sprint, only to have half the CI/CD pipeline explode. So they revert the change, leave a comment in the code, and walk away.

These aren’t horror stories. These are normal stories. The day-to-day decisions that prioritize shipping over security. Not because anyone’s being reckless, but because the system incentivizes getting things working, not getting things right.

And that’s the heart of it: convenience beats correctness, almost every time. When the choice is between writing a granular IAM policy or using an existing one that mostly works, the shortcut wins. When enforcement breaks the build, the policy is disabled. When no one owns the permissions model, nobody fixes it — and everyone just hopes it doesn’t matter.

In most teams, least privilege isn’t a guiding principle. It’s a best-effort aspiration. A checkbox in a security doc. A nice-to-have that only matters after the incident.

Until then, nobody touches it.

The Social Layer Nobody Talks About

Least privilege isn’t just a technical ideal. It’s a social minefield.

We like to imagine that access is a clean, objective thing — a matter of scopes and permissions, roles and resources. But under the surface, access is emotional. It’s tangled up in status, trust, and team politics in a way no permission schema can capture.

Asking for access makes people feel small. It signals that they’re on the outside looking in, that someone else gets to decide what’s important, what’s allowed, and what isn’t. Most people won’t say that out loud, but you can feel it in the hesitation. The slightly-too-apologetic Slack message. The “just checking if maybe...” tone. Nobody wants to look like they don’t have access to the thing everyone else seems to already have.

Denying access, meanwhile, feels even worse. No matter how tactfully it’s phrased — “just following best practices,” “let’s keep access tight” — it lands like a personal judgment. You’re the bottleneck. You’re not being helpful. You’re the one who doesn’t trust the team. There’s a reason people hate security reviews, and it’s not the paperwork — it’s the tension.

Inside most teams, everyone knows who has access to what — and also who shouldn’t, but does. Nobody wants to bring it up. Nobody wants to say, “Hey, should this staging lambda really have production write access?” Because what if it breaks something? What if it slows someone down? What if it leads to an awkward conversation with someone senior?

So we don’t say it. We avoid the hard conversation. We take the path of least resistance — because it’s socially safer than the path of least privilege.

There’s no Jira ticket for that.

The truth is, most permission sprawl doesn’t come from malicious actors. It comes from normal people trying not to be assholes. Developers who just want to get unblocked. Managers who don’t want to micromanage. Infra leads who don’t want to make enemies.

We’ve built systems where saying yes is easy and saying no requires a political finesse that most people would rather avoid. And then we’re surprised when everyone ends up with more access than they should.

Least privilege fails not because we don’t understand the policy — but because we don’t want to risk being the person who enforces it.

Who’s Actually Responsible?

When an engineer accidentally wipes a production table because their CLI still had superuser permissions, who’s at fault?

Is it the engineer who made the call?

The platform team that handed out the role?

The manager who didn’t question the access request?

The security lead who didn’t review entitlements?

The previous engineer who created the role and left six months ago?

Everyone has a hand in it. And that’s exactly the problem. The real failure of least privilege isn’t just a technical oversight — it’s structural ambiguity. It’s what happens when everyone assumes someone else is keeping the system clean. In practice, access control lives in this weird no man’s land between engineering, IT, security, and compliance — and often belongs to none of them meaningfully.

Ask a random engineer at a mid-sized company who owns access management, and you’ll get a shrug. Or worse, an answer that sounds plausible but falls apart under scrutiny:

“Oh, we have Terraform for that.”

“Oh, that’s handled by Okta.”

“Oh, I think SecOps takes care of it.”

There’s always a tool. Always a process. But no one with actual accountability. Why? Because owning access is high-risk and low-reward.

Get it right? Nobody notices.

Get it wrong? You blocked someone, or worse, caused downtime.

So we don’t own it. We inherit it. We duct-tape around it. We rationalize our way out of it.

And the problem compounds because even if someone wanted to take full ownership, they probably couldn’t. Most companies don’t have centralized visibility into all the places access is granted — not across cloud providers, CI/CD platforms, vendor tools, SaaS dashboards, and whatever personal scripts are still hitting prod from someone’s laptop.

Least privilege fails because it requires system-level coordination, but we keep approaching it like an individual decision. You can’t fix it at the level of one pull request, one IAM policy, or one department. The permission sprawl isn’t isolated — it’s systemic.

So when we say “the org failed,” that’s not a cop-out — that’s the point. No individual can enforce least privilege in isolation. But everyone can quietly help erode it.

It’s Not Just Access. It’s Trust.

Least privilege is supposed to be about safety. Reducing blast radius. Minimizing risk.

But underneath the YAML files and IAM policies, it's about something harder to define — and harder to control: trust.

We say we want systems that default to distrust, that verify before they grant, that limit what any one service — or person — can do. But we build teams that run on shortcuts, favors, assumptions, and Slack messages sent during deployment windows. We build systems that mirror us: inconsistent, overloaded, and quietly afraid of being the one to say no.

Because saying no breaks things. Saying no slows things down. Saying no makes people uncomfortable.

So instead, we say yes. Or we say nothing. Or we look the other way and let the next person deal with it.

This isn’t a problem that gets solved by better tooling. Not entirely. It gets solved when teams are willing to confront the tension between access and accountability — and sit with it, instead of bypassing it.

It’s easy to design systems that trust no one. It’s much harder to build teams that do the same — and still function.

Until we learn how to do that, least privilege will keep failing.

Not because we don’t understand it. But because we don’t want to live by it.